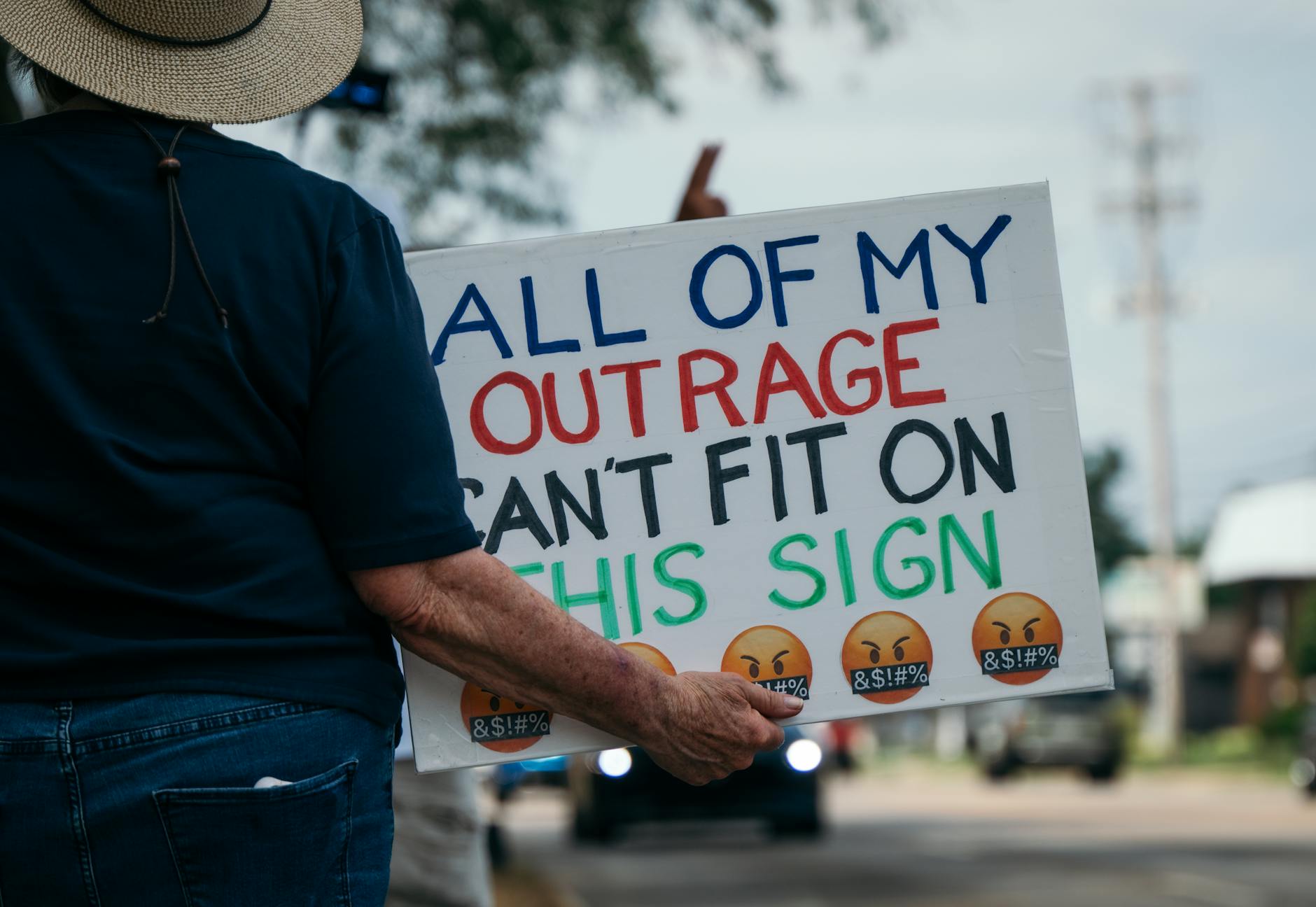

Christmas should be one of the gentlest moments in our shared cultural life, a season of light breaking into darkness, of compassion stretching itself wide enough to hold everyone. Yet in recent years, it’s been unsettling to watch Christian nationalists try to hijack it. They frame Christmas as a symbol of cultural supremacy, a line in the sand, a test of loyalty to a particular version of identity. It turns something soft into something sharp, something generous into something guarded, and it jars with the spirit of the season.

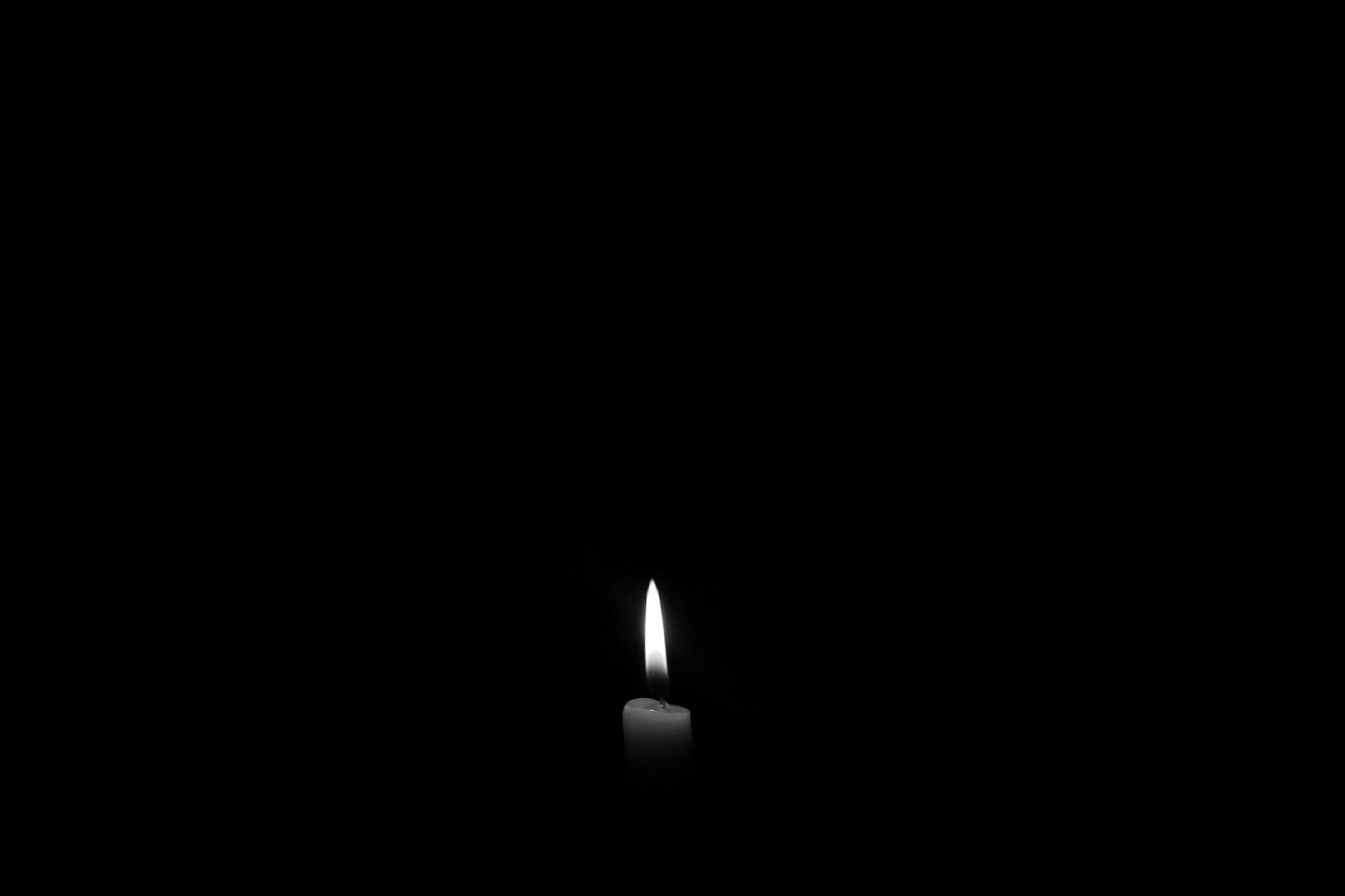

Because at its heart, Christmas has never been about drawing boundaries. It’s about hospitality, humility, and a love that refuses to stay small or confined. It tells a story of welcome that begins on the margins, in obscurity, in vulnerability. When people attempt to pull Christmas into a narrative of exclusion or cultural fear, they aren’t defending it, they’re distorting it. They miss the quiet courage of the story, the way it invites us to see strangers as neighbours and neighbours as cherished parts of a shared human family.

The good news is that Christmas still holds its shape. It keeps nudging us toward kindness, solidarity, and the courage to imagine a broader, softer way of being together. And no matter how loudly others try to claim it as a weapon in a culture war, it keeps slipping through their fingers, returning again to warmth, generosity, and the beautifully simple call to make room for one another.