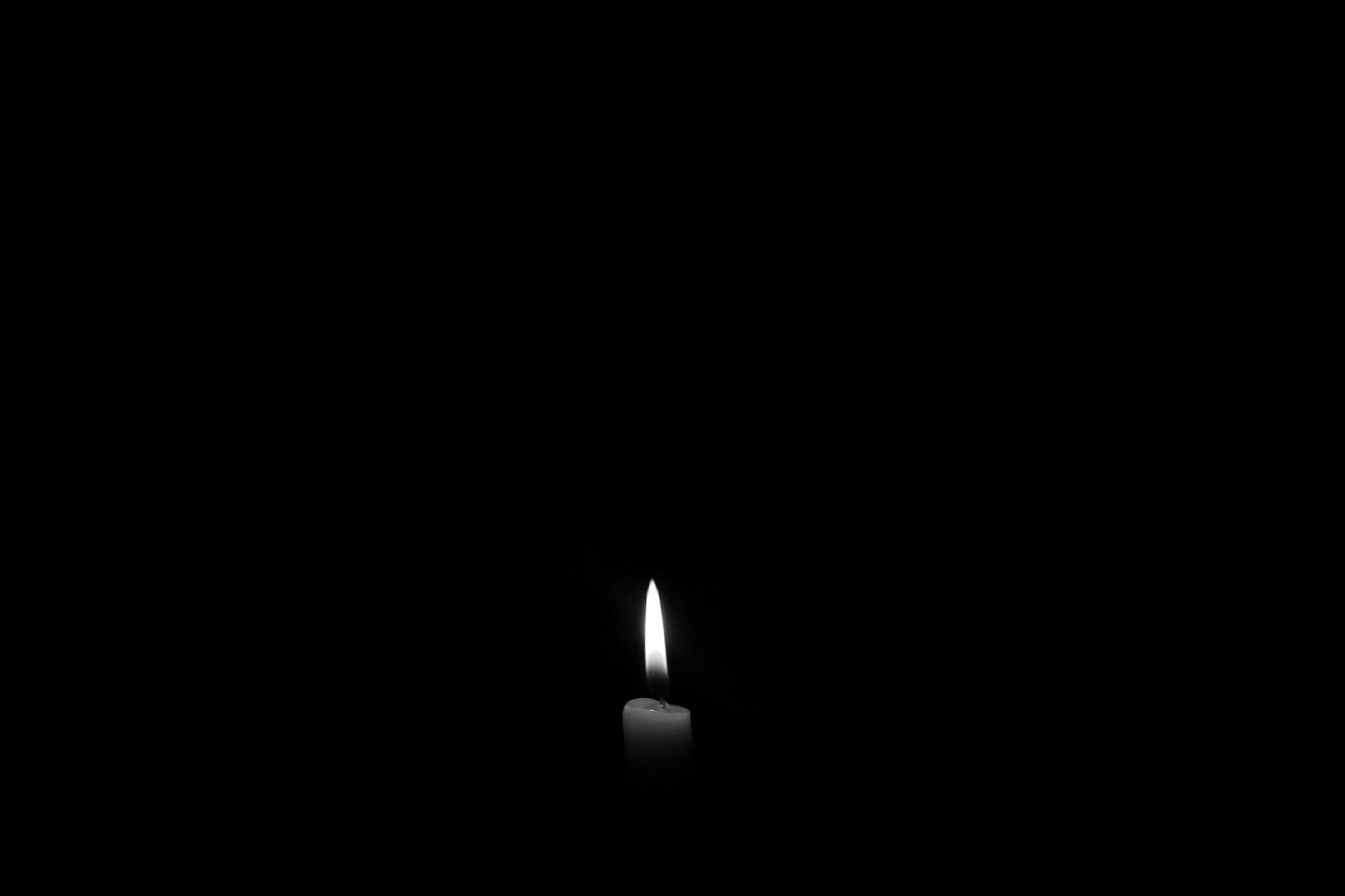

When St Andrew’s Day falls on the first Sunday in Advent, the themes of both occasions sit naturally together. Andrew is remembered as the disciple who recognised something stirring in Jesus before many others did, responding with a straightforward willingness to follow. His simple announcement, “We’ve found the Messiah” in John’s Gospel, has the feel of a light being switched on rather than a dramatic revelation. Advent begins with that same sense of early illumination: the quiet awareness that something significant is approaching, even if it isn’t yet fully seen.

The first Sunday in Advent often highlights Jesus’ call to stay awake and keep watch in Matthew 24:42–44. This isn’t a demand for anxiety, it’s a reminder to pay attention. Andrew’s life echoes that posture. He listened, observed, and took practical steps towards what he sensed God was doing, then encouraged others to come and see for themselves.

Seen together, St Andrew’s Day and Advent’s beginning underline a simple pattern of faith: noticing, responding, and preparing. They point towards the value of small beginnings, steady attentiveness, and readiness for the arrival of light, peace, and renewal.